Chapter 4 A catalogue of pedagogical patterns

4.1 Introduction

In this chapter, we present a collection of patterns that are particularly aligned with teaching and learning with Jupyter. Each pattern is targeted at specific learning goals, audiences, and teaching formats. With those in mind we describe each pattern and its pedagogical features that support the learning goals, present a practical example, and close each with any potential pitfalls you would want to be aware of.

4.2 Shift-Enter for the win

Description:

Instead of reading a static chapter about a topic, the learners read

and execute code, as well as potentially interact with a widget to

explore concepts. Starting from a complete notebook, the instructor or

learner runs through the notebook cell-by-cell by typing SHIFT + ENTER.

Example:

The notebook (or a collection of notebooks) can be used as an

alternative to a static textbook on a topic.

Learning goals:

This pattern can be used to introduce a topic or promote awareness

about a set of tools. Additionally, it can serve as documentation that

provides a tour of an application programming interface (API).

Audience(s):

Depending on the style of the notebook, this pattern can be used for a spectrum

of programming abilities.

Format (lecture / lab / …):

This pattern can be used as an alternative to a static textbook. In a

tutorial, a complete notebook can be used to provide a tour of an

application programming interface (API) of a software package.

Features:

One benefit of this approach is that learners have a complete working

example which they can adapt or build from. It provides opportunity

for richer interaction than a static textbook.

Pitfalls:

This style does not prompt much engagement with students. Having a

class that interactively works through a notebook can lead to some

students finishing much faster than others (e.g., racing through

SHIFT + ENTER). Breaking long notebooks into many smaller ones can help

with the pacing in a lecture. Having a master notebook serve as the

table of contents can then help students navigate through the

class. Notebooks can be linked in a markdown cell as:

[Notebook 1](part1.ipynb)4.3 Fill in the blanks

Description:

To focus attention on one aspect of a workflow, the

scaffolding and majority of the workflow can be laid out and some

elements removed with the intent that students (or the instructor

during a demo) fill in those pieces. The exercise might be accompanied

by a small test that the code should pass, or a plot, or value which

the code should generate if correct.

Example:

A fundamental concept in computing is the use of a for loop to

accumulate a result. A fill-in-the-blank exercise demonstrating an

accumulator could lay out the initialization, provide the skeleton of

the for loop and include plotting code, with the aim being that

students write the update step inside the for loop.

Related patterns:

This pattern is similar to Target practice; a difference is that

Target Practice often focuses on a bigger step in a multi-step

process. Fill in the Blank exercises tend to be smaller and more

immediate.

Learning goals:

This pattern focuses attention on a component of a task and provides

the benefit of demonstrating how that component fits into the bigger

picture or a larger workflow. It can be an effective approach for

taking students on a tour of an API, requiring that they use the

documentation of the software, or for focusing attention on one aspect

of an multi-step computational model.

Audience(s):

This approach can be used with a range of students, from those who are

first being introduced to computing concepts to those who have

significant experience.

Format (lecture / lab / …):

Assignments and labs can adopt this approach (nbgrader can be used to

help with marking). It can also be used in a lecture or tutorial

setting where the instructor demos how to fill in the blank.

Pitfalls:

Some students don’t find this approach engaging. In particular, if the

exercise is too simple for the level of programming competency of the

students, it can be perceived as a “make-work” task.

4.4 Target Practice

Description:

The Target Practice pattern focuses the learner’s attention on one component

of a multi-step workflow. The instructor provides all workflow steps except

the one which is the focus of the exercise; the student will implement the

“target” step within a notebook.

Example:

In a climate science assignment, the notebook that is given to students

provides code for fetching and parsing 20 years of hourly average temperature

data from a public database. Students are asked to design an algorithm for computing

yearly average temperature and standard deviation. Following this, the plotting code

which plots the yearly temperature with error-bars showing the standard deviation

is also provided to the students.

Related patterns:

This pattern is similar to [Fill in the Blank] exercises. Fill in the Blank

exercises are typically smaller and more immediate, while Target Practice

exercises tend to be larger (e.g. an entire step in a multi-step process).

Learning goals:

The aim of a Target Practice exercise is to focus attention on one

component of a workflow and practice skills for solving that component.

It can also be used to reflect on broader consequences of choices made

in the target step of an integrated workflow or analysis.

Audience(s):

This approach assumes some programming competency as learners are

typically asked to start from scratch on the step that they are

practicing.

Format (lecture / lab / …):

This approach is readily used in assignments or labs.

It can also be used in an in-class demo where the instructor live-codes

the missing component. It is beneficial if preceeding steps have been discussed

in earlier lectures.

Pitfalls:

As there is more freedom in the implementation, this approach is typically

more engaging than a Fill in the Blanks approach. However, starting from

more of a “blank slate” can require more instructor input in order to

get students started. Unit tests and pointers to useful library functions

are often helpful, but may over-constrain the space of solutions, thereby

reducing the level of creativity and problem solving expected from students.

The amount of guidance should be carefully calibrated to the class and can

be adjusted by giving tips in response to formative assessments. Working in

small groups can help mitigate the risks of students having trouble getting

started or pursuing tangents.

4.5 Tweak, twiddle, and frob

Description:

Students are given a notebook with a working example. They start by reading the text,

running the code, and interpreting the results. Then they are asked to make a series of

changes and run the code again; the changes can be small (tweaks), medium-sized (twiddles),

or more substantial (frobs). For the origin of these terms, see

The New Hacker’s Dictionary (Raymond, 1996).

Offering manipulations on a range of scales allows students to interact with notebooks in ways that suit their background and styles. Students who feel overwhelmed by the technology can get started with small, safe changes, enjoy immediate success, and work their way up. Students with more experience or less patience can make more radical changes and learn by “destructive testing”.

Examples:

In machine learning there are many steps to implementing an effective algorithm:

- Understand a problem

- Identify the proper machine learning algorithm to create the desired results

- Identify data and feature sets

- Optimize the configuration of the machine learning algorithms

We can write machine learning notebooks that allow students to modify parameters and interact at multiple levels of detail:

- twiddle hyper parameters to quickly see minor improvements in the results.

- tweak feature sets to create new models for a bigger impact

- frob by replacing the machine learning algorithm with a new algorithm or a new version

This pattern is particularly suitable for examples with a lot of parameters.

Learning goals:

This pattern helps students acquire domain knowledge by seeing the relationship

between parameters and the effect they have on the results. It can also help students

learn new notebook use patterns

This pattern is similar to “notebook as an app”; a difference is that in this pattern the code is more visible to the students, which can help orient them if they will make bigger changes in the future.

Audience(s):

This pattern can work with students who have no programming experience; they only

need to be able to edit the contents of a cell and run a notebook. It can also work

with students who have no background with the domain; they can learn about the domain

by exploring the effect of parameters.

Format (lecture / lab / …):

This pattern lends itself to a workshop format, where students are guided through a

notebook with time-boxed opportunities to experiment. It also lends itself to pair

programming, where a navigator can suggest changes and a driver can implement them.

Features:

Can help students overcome anxiety about breaking code, and build comfort with

self-directed exploration.

Pitfalls:

One hazard of this pattern is that students might have trouble getting started,

so you might suggest a few examples; however, another hazard is that, if you provide

examples, students will do what they are told and fail to explore. A third hazard

is that the changes a student makes might be too unorganized; in that case the

effect of the parameters might be lost in the chaos.

Enabling technologies:

Ideally the students should work in some kind of version control system that lets

them revert to a previous version if they break something (and don’t know how to

fix it). Note that undo and redo, Ctrl-z and Ctrl-y, can be used to traverse

deep history within each cell, but not across cells.

4.6 Notebook as an app

Description:

Notebooks can be used to rapidly generate user interfaces where

students and instructors can interact with code through sliders,

entry boxes, and toggle buttons. The code can run numerical simulations

or perform simple computations, and the output is often a graph or

image.

Example:

In geophysics, a direct current resistivity survey involves connecting

two electrodes to the ground through which current is

induced. Current flows through the earth and the behavior depends

upon the electrical resistivity of the subsurface structures; current

flows around resistors and is channeled into conductors. At interfaces

between conductors and resistors, charges build up, and these charges

generate electric potentials which we measure at the surface of the

earth. Each of these steps can be demonstrated through a simulation

where students or the instructor builds a model, and views the

currents, charges and electric potentials.

Related patterns:

Top-down sequence

Learning goals:

This approach can be effective for focusing on domain-specific

knowledge and facilitating the exploration of models or computations.

Audience(s):

This style can be effective for students with minimal programming

experience as they do not have to read, write, or see the code.

Format (lecture / lab / …):

In lecture, this style of notebook can be used by an instructor to

methodically walk through a concept step-by-step. It is also useful

for promoting in-class engagement as students can suggest different

parameter choices and instructors can adapt the input parameters based

on students’ questions.

In a lab or assignment, the notebook can be used as a “app” around which questions and exercises are built.

Features:

Notebooks as apps can be used to promote engagement with students in

lecture. In labs, assignments or in-class activities, this approach

lowers the barrier-to-entry for students to explore complex models.

Pitfalls:

It is important to have well-structured exercises and questions for

students to address with the app. As with any app, simply asking

students to play with it does not promote productive engagement.

In structuring an exercise for students, we recommend putting instructions and questions in a separate document rather than in the notebook. If students view the notebook as an app, they often want to interact with it rather than read it. By having instructions and questions that go alongside the notebook, they can have the app in view while reading.

This approach is not intended to be used for developing students’ programming skills.

Enabling technologies:

Widgets, domain-specific libraries such as simulation tools.

4.7 Win-day-one

Description:

A win-day-one exercise brings learners to the answer quickly and

concisely, almost like a magic trick, and then breaks down and

methodically works through each of the steps, revealing the magician’s

tricks. It generally involves multiple notebooks: the first notebook

being the “win” which shows the workflow end-to-end, and subsequent

notebooks breaking down the details of each component of the workflow.

Example:

To solve a numerical simulation using a finite volume approach, a mesh

must be designed, differential operators formed, boundary conditions

set, a right-hand side generated and then the system

solved. Naturally, there are important considerations for each

step. For even a moderately sized problem, sparse matrices are

necessary in order to keep memory usage contained, the mesh must be

appropriately designed in order to satisfy boundary conditions, and

the solver needs to be compatible with the structure of the system

matrix. These details are critical for assembling a numerical

computation, but if introduced upfront, they can overwhelm the

conversation.

In a win-day-one approach, learners are first shown a concise example,

in which many of the details are abstracted away in functions or

objects. For example, methods such as get_mesh, get_pde, and

solve abstract away the details of mesh design, creating

differential operators and solving the set of equations. In subsequent

notebooks, the workflow is tackled methodically, and the inner

workings of each component discussed.

Related patterns:

Top-down sequence, Proof by example, disproof by counterexample

Learning goals:

This can be an effective approach for introducing complex processes,

providing context for how each of the components fits together, and

focusing attention.

Audience(s):

This style can be effective for a spectrum of student audiences from

those with some programming experience to those with significant

experience.

Format (lecture / lab / …):

This can be effective for tutorials and workshops, and can be used over

multiple lectures. This can be useful when introducing new topics to help hook

students because they accomplish significant results early in the learning

process.

Pitfalls:

One hazard of the “win-day-one” is that the “win” is overwhelming (too

much detail) or too magical (too little detail). An appropriate level

of detail needs to be selected so that each of the components of the

workflow is demonstrated, but at a high-level.

4.8 Top-down sequence

Description:

Particularly in STEM, the default sequence of presentation is

bottom-up, meaning that we teach students how things work (and

sometimes prove that they work), before students learn how to use

them, or what they are for.

Notebooks afford the opportunity to present topics top-down; that is, students learn what a tool is for and how to use it, before they learn how it works.

Examples

In digital signal processing, one of the most important ideas is the discrete Fourier transform, which depends on complex arithmetic; in a bottom-up approach, we would have to start by teaching or reviewing complex numbers, which is not particularly engaging.

In contrast to writing the mathematics on paper, in a notebook students can use a library that does the discrete Fourier transform for them, so they understand what it is used for, and see the value of learning about it, before we ask them to do the work of understanding it.

Some important methods are intrinsically leaky abstractions that require user expertise to use effectively and reliably. This is often because truly reliable solutions (if they exist) are disproportionately expensive for common cases. Numerical integration and methods for discretizing and solving differential equations often fall in this category. In addition to gaining intuition before diving into the details, the top-down pattern can be used to expose these leaks as motivation to understand the methods well enough to explain and correct for the shortcomings. For example, one can motivate convergence analysis and verification (Roache, 2004) by showing a solver that passes some consistency tests, but does not converge (or converges suboptimally) in general; or motivate conservative/compatible discretizations by showing a solver that has been verified for smooth solutions produce erroneous results for problems with singularities or discontinuities. Consider, for example, Gibbs and Runge phenomena, instability for Gram-Schmidt (Trefethen & Bau, 1997), entropy principles (LeVeque, 2002), eddy viscosity (Mishra & Spinolo, 2015), and LBB/inf-sup stability and “variational crimes” (Brenner & Scott, 2008; Chapelle & Bathe, 1993).

Learning goals:

This pattern is useful for building intuition, context, and motivation before

introducing technical domain content instead of building up in a setting where

implementation details often take center stage.

Audience(s):

This pattern can be effective with students who have limited programming skills,

as they can use a library and see the results without writing much, if any, code.

Format (lecture / lab / …):

This pattern can be used in a single class session or homework, or spread out over

the duration of a course; for example, students could use a tool on the first day

and find out how it works on the last.

Features:

Shows students value and rewards their attention quickly (see Win-day-one).

Pitfalls:

A potential hazard of this pattern is that students might be less motivated to

learn how the tool works if they think they have already understood what it is

for and how to use it. This hazard can be mitigated by making obvious the additional

benefit of understanding how it works (assuming that there actually is one—it is

not enough to assert that knowing how it works is necessarily better).

“Interesting” failure modes (see examples above) discovered by students while

trying to solve a problem are great for motivating deeper understanding.

4.9 Two bites at every apple

Description:

This pattern involves writing an activity that can address multiple audiences

from different perspectives at the same time. This can be powerful when

addressing a mixed audience of students.

Example:

Say you have a group of students, some of whom are computer science students

and some of whom are physics students, and ask them to come up with two

expressions for computing the centroid of an area. The computer science

students will be tasked with a description that involves adding up discrete

pieces of areas with for loops and the physics students tasked with using the

integral definition. When the students come up with their expressions they can

then pair up with someone from the other background where they can attempt to

explain how their approach matches the other and compare their final answers.

Learning goals:

Ability to translate from one field/language to another. Explain complex topics

to someone from a different field.

Audience(s):

Groups which are composed of disparate backgrounds.

Format:

This format involves both individual and group work but can be used in a lab or

lecture setting. The basic notebook would include an overview of the problem

and then pose questions whose answer is the same but is worded for the

different audiences. There can be a single notebook that contains both

questions so that students can fill in their peers solution once they

understand it or there can be separate notebooks for each group so they do not

get distracted by the other question.

Features:

Group work and peer teaching has been shown to be effective at not only

reinforcing student knowledge but also at introducing students to new concepts.

Pitfalls:

It can be difficult to construct questions for each audience that require equal

amounts of difficulty.

4.10 Coding as translation

Description:

Converting mathematics to code is a critical skill today that many students,

especially those without strong programming backgrounds, struggle to do.

Explicitly taking an equation and translating it step-by-step to the code can help

these students make the transition to attaining this skill.

Example:

Say you wanted to show the translation of matrix-vector multiplication from equation

to a numerical computation. This would involve setting up and explaining the

mathematics and suggesting replacing the sums with loops and initializing the sum properly.

Learning goals:

Translating mathematics to code (and vice versa)

Audience(s):

Learners who understand the theory but struggle with the programming side of things.

Format:

This type of pattern is often best served as a notebook with some explanatory text and

possibly some scaffolded code so that a student can focus on the critical areas.

This can be done as easily as a lab exercise or in lecture with perhaps some time held

out for the students to solve it themselves before moving forward. It is critical to this

pattern that there is a clear connection between the mathematical symbols (such as the

summation) to the code (such as the for loops).

Features:

This pattern can work to lower the barrier for students with low programming knowledge

to take on more complex tasks.

Pitfalls:

If the exercise is not properly scaffolded, namely it is too complex, students can be turned off.

This is especially true if the code example is too complex with too many steps.

For instance avoiding compound operators in the example above (+=) can help student retention.

4.11 Symbolic math over pencil + paper

Description:

Your objective is to convey an understanding of a physical system governed by a

complicated mathematical system. Working out the algebra is necessary to

uncover the fundamental behavior of the system, but how to do the algebra is

not the goal of the lesson. In this case, you want to see the algebraic result

and then teach the students the underlying meaning of the system,

Example:

The Euler equations for hydrodynamics are a system of partial differential equations

governing conservation of mass, momentum, and energy. Their mathematical character

admits wave solutions, and the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the system in matrix

form are important to understanding the physical behavior of the density, pressure,

velocity, etc., in the system. Working out the eigenvalues with pencil and paper is tedious,

and not the objective of the lesson. In this case, we can use a symbolic math library

like SymPy (Meurer et al., 2017) to do the mathematical analysis for us, finding the eigenvalues

and eigenvectors of the system, and we can then use this result to continue our theoretical

discussion of the system.

Learning goals:

Students will see how to do symbolic math that arises in their theoretical analysis.

Audience(s):

STEM students that want to focus on understanding a mathematical system without

worrying about the algebraic details.

Format:

This works well as a notebook that acts as a supplement to the main lecture.

Since the goal of the lecture is the theory, the notebook can [TODO: complete]

Features:

Abstracts the details of mathematics that is secondary to the discussion at hand

into a separate unit that students can explore on their own.

Pitfalls:

This only works well in the case that the algebra is not essential to the main

learning goals, but rather is simply something that must be done to get to the main goal.

4.12 Replace analysis with numerical methods

Description:

Some ideas that are hard to understand with mathematical analysis are easy to

understand with computer simulation and numerical methods.

In the usual presentation, students see and learn to do mathematical analysis on a series of simple examples, and resort to numerical methods only when necessary. In an alternative pattern, students skip the analysis and start with simulation and numerical methods, optionally visiting analysis after gaining practical experience.

Examples:

In statistics, hypothesis testing is a central idea that is notoriously

difficult for students to understand. Students learn methods for computing

p-values in a series of special cases, but many of them never understand the

framework, or what a p-value means. The alternative is to compute sampling

distributions and p-values by simulation; anecdotally, many students report

that this approach makes the framework much clearer. Such simulation can also

be used to drive home points about misconceptions held by most students and

instructors (Haller & Krauss, 2002).

Similarly, in queueing theory, there are a few analytic results that apply under narrow conditions; when those conditions don’t apply, there are no analytic solutions. However, queueing systems lend themselves to simulation and visualization, and in simulation it is easy to explore a wide range of conditions.

And again, with differential equations, there are only a few special cases that have analytic solutions; the large majority of interesting, realistic problems don’t.

Learning goals:

This pattern is primarily about helping students see the big ideas of the

domain more clearly, but it is also a chance to develop their programming

skills. It also provides students with tools that are likely to be needed if

they encounter similar problems in the real world, where analytic methods are

often inapplicable, fragile, or complicated to use effectively.

Audience(s):

This pattern requires students to have some comfort with programming, although

it would be possible for them to get some of the benefit from seeing examples

without implementing them. Non-programmers can use this pattern via prepared

notebooks; see Win Day One.

Format (lecture / lab / …):

This pattern can be used for in-class activities or homework.

Features:

Students can understand general ideas without getting bogged down in the

details of special cases; and they are able to explore more interesting and

realistic examples.

Pitfalls:

If students are not comfortable programmers, they can get bogged down in

implementation details and debugging problems, and miss the domain content

entirely. It is important to scope the implementation effort to suit the full

range of students in the class. Pair programming can help mitigate these

problems, especially if every pair has at least one student with programming

skills, and if students are coached to pair program effectively (without

letting the more experienced student dominate).

4.13 The API is the lesson

Description:

When students work with a software library, they are exposed to functions and

objects that make up an application programming interface (API). Learning an API

can be cognitive overhead; that is, material students have to learn to get work

done computationally, but which does not contribute to their understanding of

the subject matter. But the API can also be the lesson; that is, by learning the API,

students are implicitly learning the intended content.

Example:

In digital signal processing, one of the most important ideas is the relationship

between two representations of a signal: as a wave in the time domain and as a

spectrum in the frequency domain. Suppose the API provides two objects, called

Wave and Spectrum, and two functions, one that takes a Wave and returns a Spectrum,

and another that takes a Spectrum and returns a Wave. By using this API, students

implicitly learn that a Wave and a Spectrum are equivalent representations of the

same information; given either one, you can compute the other.

Related patterns:

Top-down sequence

Learning goals:

This pattern is useful for shifting students’ focus from implementation details

to domain content.

Audience(s):

This pattern is most effective if students have some experience using libraries

and exploring APIs.

Format (lecture / lab / …):

This pattern

TODO: complete

Pitfalls:

A hazard of this pattern is that students sometimes perceive the costs of learning the

API and do not perceive the benefits. It might be necessary to help them see that

learning the API is part of the lesson and not just overhead.

4.14 Proof by example, disproof by counterexample

Description:

In many classes, students see general results derived or proved, and then use those

results in programs. Notebooks can help students understand how these results work

in practice, when they apply, and how they fail when they do not.

Example:

In statistics, the Central Limit Theorem (CLT) gives the conditions when the

sum of random variables converge to a Gaussian distribution. Students can

generate random variables from a variety of distributions and test whether the

sums converge and how quickly.

The classical Gram–Schmidt is unstable while the modified method is stable. Students can find matrices for which this instability produces obviously unusable results. They can also find matrices for which modified Gram-Schmidt produces unusable results due to its lack of backward stability, and this can be used to motivate Householder factorization and discussion of backward stability.

Some numerical methods for PDE converge with an assumption on smoothness of coefficients. Students can show how violating these assumptions leads to erroneous solutions, thus motivating discussion of conservative/compatible methods that can converge in such circumstances.

Learning goals:

This pattern is primarily useful for developing mathematical or domain knowledge,

but students might also develop programming experience by writing code to run the

examples and test the outcomes. This is especially true if the space of

(counter-)examples is “small”, such that principled exploration (e.g., by finding an

eigenvector, running an optimization algorithm, or searching a dictionary) is beneficial.

Audience(s):

This pattern requires students to have some programming experience.

Format (lecture / lab / …):

This pattern can be used for in-class activities or homework.

Features:

Helps students translate from theoretical results to practical implications,

and to remember the assumptions and limitations of theory.

Pitfalls:

This pattern requires additional time and student effort on a topic that might

not deserve the additional resources.

4.15 The world is your dataset

Description:

Notebooks provide several ways to connect students with the world beyond the classroom:

one simple way is to collect data from external sources. Data is available in many

different formats that require different software tools to collect and parse.

If a dataset is available in a standard format, like CSV, it can be downloaded from inside the notebook, which demonstrates a good practice for data integrity (going to the source rather than working with a copy) and demystifies the source of the data.

For data in tabular form on a web page, it is often possible to use Pandas to parse the HTML and generate a DataFrame. Also, for less structured sources, tools like Scrapy can be used to extract data, “scrape”, from sources that would be hard to collect manually, and to automate cleaning and validation steps.

Examples:

Datasets like the National Survey of Family Growth are available

in files that can be downloaded directly from their website, but the terms of

use forbid redistributing the data. So the best way for an instructor to share

this data is to provide students with code to input into a notebook cell,

which, when executed, will download the data set the first time the student

runs the notebook.

Many Wikipedia pages contain data in HTML tables; most of them can be imported easily into a notebook using Pandas.

Sources of sports-related statistics are often embedded in large networks of linked web pages. Tools like Scrapy can navigate these networks to collect data in forms more amenable to automated analysis.

Audience(s):

Students with limited programming experience can work with datasets in standard

formats, but scraping data might require more programming experience.

Format (lecture / lab / …):

This pattern lends itself to more open-ended project work where students are responsible

for identifying data sources, collecting data, cleaning, and validating, but it can

be adapted to more scaffolded work (see Target Practice).

Features:

Contributes to students’ feelings of autonomy and connectedness.

Pitfalls:

A hazard of this pattern is that students can spend too much time looking for data

that is not available. They might need coaching about how to make do with the data

they can get, even if it is not ideal.

Enabling technologies:

Pandas, Scrapy, R, ROpenSci packages

4.16 Now you try (with different data or process)

Description:

Students start with a complete working example provided by an instructor and

then they change the dataset or process to apply the notebook to an area of

their own choosing. This method can allow more or less fluctuation depending on

the skills of the students. For example we can allow students to select new

datasets from a list that ensures the cells of the notebook will all still work

or we can give them freedom to try new data structures or add new processes to

break the notebooks and learn as they go through the process of fixing the

broken cells.

Example:

An instructor designs a lesson in exploratory data analysis to scrape the

critics’ reviews for a specific movie from a particular movie review website and

then provide some simple visualizations. The students have a few options:

- Green Circle - replace the movie name and pick any movie they want and then step through the new notebook and see the new results.

- Blue Square - adjust the notebook to scrape users’ reviews rather than critics’ reviews and then fix any data parsing problems.

- Black Diamond - add different visualizations tailored to explore the user reviews (as opposed to the initial visualizations that are tailored for the critics’ reviews).

There are various ways to test the properties of numerical methods. For example, students can use the method of manufactured solutions to test the order of accuracy for a differential equation solver. They can also measure cost as the resolution is increased and present the results in a way that would help an analyst decide which method to use given external requirements (e.g., using accuracy versus cost tradeoff curves).

Related patterns:

Top-down sequence

Learning goals:

This pattern allows students to apply their knowledge

Audience(s):

This pattern can be tailored for students with more or less experience even in

the same course.

Format (lecture / lab / …):

This pattern is best in a lab or an interactive tutorial

Pitfalls:

A hazard of this pattern is that students may go completely off the rails and

chose datasets or new processes that have not been tested and will not work in

the timeframe allowed.

4.17 Connect to external audiences

Description:

This is in some sense the opposite of “the world is your dataset.”

Here the goal is to take a workflow or computational exploration and share it with

the world so others can see it, learn from it, reuse and remix it.

Examples:

Your students are doing an observational astronomy lab where they take data from a

telescope of a transiting exoplanet (a planet around a star other than our Sun)

and they examine the lightcurve to learn about the planet. The students present the

lab as a Jupyter notebook with a reproducible workflow that starts with reading in

their data (images), walks through cleaning and reducing the images, and then

performs photometry on the host star to produce a lightcurve. The end product is a

plot showing the star’s brightness, dimming just slightly as the unseen planet comes

between the star and earth. Elated with their result, the students want to share

their data and workflow so anyone else can redo the analysis.

Learning goals:

Reproducibility is an important part of the scientific process. Having completed

the primary scientific analysis that was the goal of the lab (obtaining a lightcurve

of a transiting exoplanet), the students now can learn reproducible science practices

by hosting their notebook on a webserver (e.g., Github) along with the data.

An essential part of making the notebook reproducible will be ensuring that the

notebook clearly lists the needed dependencies.

Audience(s):

All students—everyone should learn about reproducibility.

Format:

A self-contained notebook hosted on a webserver.

Features:

Teaches students about reproducible science workflows.

Pitfalls:

You need to be clear about the library requirements needed to run the notebook.

Also, since the data files are likely separate from the notebook, it is possible

for copies of the notebook to get shared without the data. Students may also be

shy or fearful of showing their work publicly, so explaining the benefits may

be needed to curtail their worries.

4.18 There can be only one

Description:

This pattern involves creating a competition between individual students or

teams of students. Clear goals and metrics need to be defined and then students

submit notebooks that are scored and evaluated. Competitions can span months or

be completed in a single class.

The Jupyter ecosystem support for reproducibility and data sharing make it a great environment for creating healthy competitions. Kaggle is a site that hosts many machine learning competitions using Jupyter as its underlying infrastructure and is a great place for advanced students to extend their knowledge with a chance of winning cash prizes and solving current world problems.

Examples:

Identify a machine learning problem and a labeled dataset your students can use

to train their model. Then select an evaluation metric and detail your problem

statement and rules. Finally, launch your competition and allow your students

to submit their notebooks and post their results on a public leaderboard.

Learning goals:

Creative problem solving is a key aspect of this pattern. In addition, if the

competition is team-based then the students will learn how to work in groups

and communicate effectively and share responsibilities.

Audience(s):

Students can benefit from healthy competition and working in teams, however it

is critical that a safe, fun, and engaging environment is created. Advanced

students can be pointed toward kaggle or other public competitions that may be

in their area of interest and give them a chance to test their skills in the

real world.

Format:

A competition can be defined with any metrics and rules and can be run in

multiple ways. The students can help define the rules or a simple vote can

decide the winners. For a more formal competition instructor can host free

competitions for their class hosted by Kaggle.

https://www.kaggle.com/about/inclass/overview

Features:

Teaches students about creative problem solving and teamwork.

Pitfalls:

Creating a fair competition is not trivial and considerations regarding data,

metrics, rules, and scoring may be time consuming. Competition is risky

business and effort should be made to ensure both winners and losers enjoy the

experience.

4.19 Hello, world!

Description:

In some situations (such as the first day of class of a very introductory course)

you may wish to do no more (and no less) than build confidence in the students’

abilities to be able to write a first computer program. Traditionally, the first

program written was a “hello, world” program: a program that did nothing but display

the text “hello, world” on the screen. However, these days students can have much more fun,

and step fully into the creative world of computing with very little instruction.

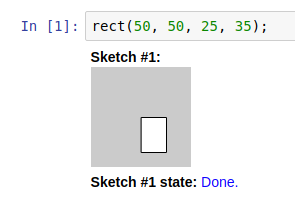

Example:

Draw a rectangle. Change the numbers, run it again, and see what happens.

Figure: a first sketch using Calysto Processing, a Java-based language designed for creating art.

Learning goals:

Reduce stress, build confidence, connect onto their personal lives. Requires that they

do learn the basics of Jupyter including: log in, open a new notebook, enter the provided code,

and execute it. Often leads to a very animated, active learning classroom activity

(“How can I change the colors?”, “How do I draw a circle?”, etc.)

Audience(s):

Beginning students.

Format (lecture / lab / …):

First day of class, in-class exercise. Build on what students already know from

typing and reading (e.g., cut and paste, read top-to-bottom).

Features:

Open ended, creative, fun.

Pitfalls:

Works best when used with a pre-installed Jupyter (see the relevant chapter).

Rather than telling students that they can do it, just do it. As a

first assignment, to cut down on the vast possibilities, we suggest

limiting the palette of options. For example, restrict their drawings

to use only a single shape, such as rectangle or triangle. We suggest

having the students draw something in their life that is important or

meaningful to them. We suggest discussing the coordinate grid for the

first assignment and sketching an idea on paper first.

4.20 Test driven development

Description:

The instructor provides tests written in a unit testing framework like unittest or doctest;

students write code to make the tests pass.

Example:

TODO: Necessary?

Learning goals:

Helps students learn a good software development process.

Audience(s):

This pattern requires students to have some programming experience.

Format (lecture / lab / …):

This pattern can be used for in-class activities or homework.

Features:

Helps students focus on the task at hand and know when they are done (at least

to the degree that the tests are complete).

Pitfalls:

Some Python unit testing frameworks are not designed to work with notebooks,

and can be awkward to use. On the other hand, nbgrader [TODO: add cross

reference to nbgrader] supports automated testing of the code students write in

notebooks; in that environment, the tests are not visible to students, which

may or may not be a bug.

This pattern requires the overhead of teaching students about the unit testing framework. Students working to make tests pass can lose their view of the big picture, and feel like they have been robbed of autonomy. This type of exercise is best used sparingly.

4.21 Code reviews

Code reviews involve a student or instructor providing feedback on someone else’s code. This pattern involves peer work as well as a means for providing feedback to students on topics other than correctness of their code but also on code readability and styling.

Example:

Present a problem to students that they must write a solution to, say computing

the square root of a number without using a built-in function but have them

write a test for their function that uses a built-in function to compute the

answer. After they are finished have the students pair up and perform peer

reviews of each other’s code, commenting not only on the way they solved the

problem, such as making up a list of pros and cons of their approaches, but

also on the readability of the code.

Learning goals:

Learn to read and understand someone else’s code. Learn to write readable code.

Audience(s):

Any group of students who are involved in coding.

Format:

Once a suitable problem is formulated in a notebook (or simply a script) then

in-class review, as with the above example, can work for peer reviews.

Alternatively students can upload their notebooks/scripts to a platform such as

GitHub and the code reviews can be done using the tools available there.

Sufficient scaffolding must be provided so that students understand the

process, how to make constructive comments and why the process is important. If

an instructor wants to review and provide feedback notebooks/scripts can be

collected and commented on with a similar explanation to students as to how

they are going to be graded (if they are).

Features:

This pattern leads to not just feedback for the person who wrote the code but

also for the reader. Code review is also a critical piece of the software

development process used in industry providing students with a view of the

process. This can also have the result of making sure that a student’s code is

readable via appropriate code styling, commenting and documentation.

Pitfalls:

Students need to be properly informed as to how the code reviews will impact

their grades, especially if peer review is used. Notebooks on GitHub are not as

easily reviewed as scripts.

4.22 Bug hunt

Description:

The instructor provides a notebook with code that contains deliberate bugs.

The students are asked to find and fix the bugs. Automated tests might be provided

to help students know whether some bugs remain unfixed.

Example:

TODO

Learning goals:

This pattern helps students develop programming skills, especially debugging (of course);

it also gives the practice reading other people’s code, which can be an opportunity

to demonstrate good practice, or warn against bad practice. It can also be used to

teach students how to use debugging tools.

Audience(s):

This pattern requires students to have some programming experience.

Format (lecture / lab / …):

This pattern can be used for in-class activities or homework.

Features:

Can be engaging and fun; develops important meta-skills.

Pitfalls:

The bugs need to be calibrated to the ability of the students: if they are too easy,

they are not engaging; if they are too hard, they are likely to be frustrating.

4.23 Adversarial programming

Description:

This pattern involves participants writing a solution to a problem and tests

that attempt to make the written solution fail. This pattern can be done in

many ways including having students complete the tasks and pair up and exchange

solutions/tests or having the instructor writing the solution and the students

then write the tests.

Example:

Students are tasked to write a function that finds the roots of a polynomial

specified via some appropriate input. They are also asked to write a set of

tests that their function passes and fails on. When students have completed

these tasks they then exchange their notebooks and use the tests they wrote on

their peer’s function. Finally they will discuss any differences in their

approaches and whether they can come up with ways to not fail each other’s

tests or if the tests provided are invalid.

Learning goals:

Learn to write unit tests. Think critically on how an adversary might break their solution.

Audience(s):

Any group of students who are involved in coding.

Format:

Decide on a sufficiently complex problem that may have non-trivial tests

written for it and write up the question in a notebook. Then as an in-class

activity or lab start the discussion regarding the tests. If appropriate the

instructor can collect notable tests written by students and also share those.

Features:

Provides a means for students to think critically about a problem they are

solving and how someone might break their solution. Also can provide a learning

activity with a form of competition involved, which can then lead to an award

system if desired.

Pitfalls:

With competition come dangers if students are not properly scaffolded so that

they can provide constructive feedback. Some problems and/or solution

strategies are vulnerable to many corner cases, leading to tedious whack-a-mole

or fatalism that may distract from learning objectives.

References

Brenner, S. C., & Scott, L. R. (2008). The mathematical theory of finite element methods. Springer Verlag.

Chapelle, D., & Bathe, K. J. (1993). The inf-sup test. Computers and Structures, 47, 537–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/0045-7949(93)90340-J

Haller, H., & Krauss, S. (2002). Misinterpretations of significance: A problem students share with their teachers. Methods of Psychological Research, 7(1), 1–20. Retrieved from http://www.dgps.de/fachgruppen/methoden/mpr-online/issue16/art1/haller.pdf

LeVeque, R. J. (2002). Finite volume methods for hyperbolic problems. Cambridge University Press.

Meurer, A., Smith, C. P., Paprocki, M., Čertı́k, O., Kirpichev, S. B., Rocklin, M., … Scopatz, A. (2017). SymPy: Symbolic computing in Python. PeerJ Computer Science, 3, e103. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.103

Mishra, S., & Spinolo, L. V. (2015). Accurate numerical schemes for approximating initial-boundary value problems for systems of conservation laws. Journal of Hyperbolic Differential Equations, 12(01), 61–86. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219891615500034

Raymond, E. S. (1996). The new hacker’s dictionary. MIT Press.

Roache, P. J. (2004). Building PDE codes to be verifiable and validatable. Computing in Science & Engineering, 6(5), 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCSE.2004.33

Trefethen, L. N., & Bau, D. (1997). Numerical linear algebra. Society for Industrial Mathematics.